When I was sixty, I had a revelation I should have had when I was six. Between classes at work, I liked to lie on my back on a bench outside and gaze at the sky. I was lying there on a warm summer day, the sky clear blue above and to the north over Lake Erie but with a bank of cumulus clouds looming from the southwest. I looked up at the emptiness above, closed my eyes, then opened them and saw a faint puff of white overhead. As I watched, it slowly grew, took on a visual substantiality as it drifted southward where it melded with another small cloud I’d overlooked.

I wondered where it had come from.

Then out of the corner of my eyes I caught sight of another tiny, thin, puffy, slow emergence drifting to join the other.

Then I saw it.

Directly overhead a cloud emerged from nothing, out of thin air in the most literal sense. Growing, transforming, drifting to join the others that were now disappearing against the mottled gray background of the cumulus bank. Over and over I watched the emptiness above give forth faint wisps that grew and drifted away. I saw clouds being born.

As a rational adult I understood what I witnessed. My location was perhaps a thousand yards south of the Lake Erie. As air moved from the lake over land ,humidity condensed with the change in temperature. But this simple atmospheric phenomenon struck me as miraculous because it upset the unquestioned assumptions I had used since childhood to understand the world: that everything comes from somewhere, that what is undetectable to the sensate mind doesn’t exist, that meaning is governed by the mind’s ability to trace the origins of things.

This miracle proved to me by personal experience (and isn’t personal experience the only irrefutable authority for truth?) that nothing gives forth something. I suddenly saw what hadn’t been there, or what had been there but had been invisible, as the humidity was there before the cloud was born.

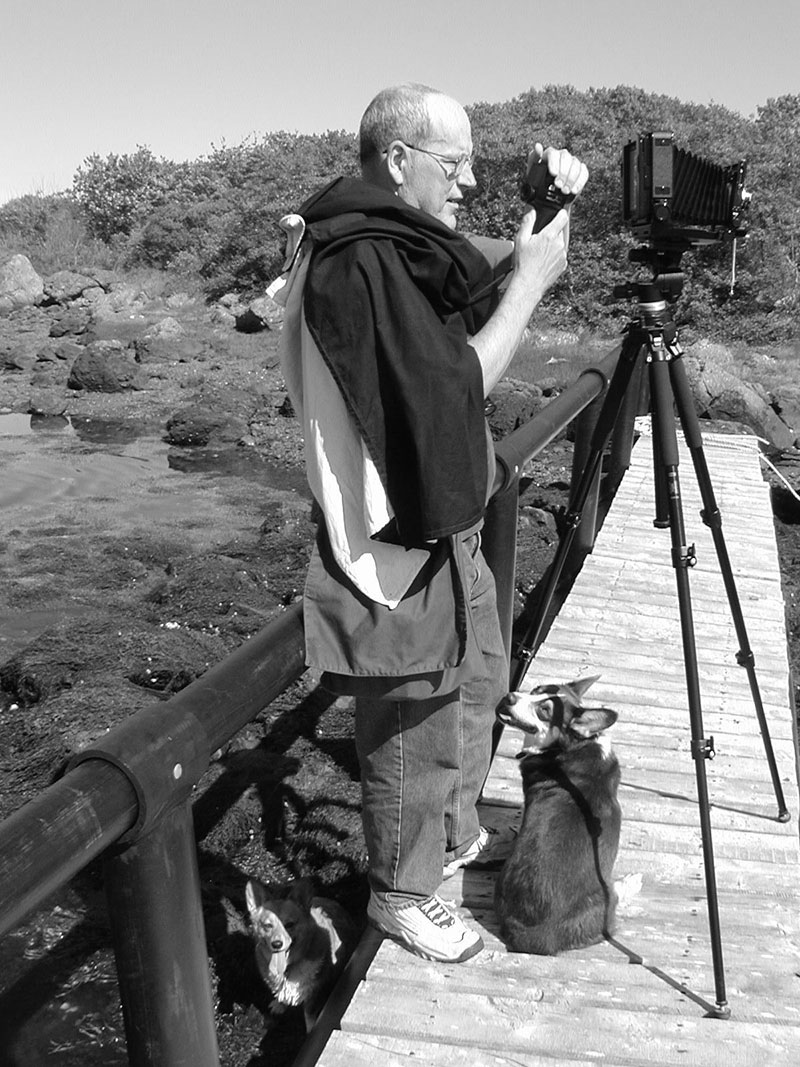

Cloud watching has taught me what little I know about the creative process. As an artist, what I create is the invisible passing through a temporary form. My images, like clouds, come from nowhere and become now here.