Because I usually prefer a square print and work with rectangular negatives, I have to pay particular attention to cropping. I hardly ever see the edge of my image through the lens. When I shoot I am drawn to an element of light and I place it within the lens frame where I think it might eventually be in the print, but I’m not fanatical about it. Cropping in the dark room adds another stage to the creative process. It can be done with a degree of deliberation not possible when shooting in the field in ambient light that is always changing.

In determining the edge of an image I consider three options: closed frame, open frame, and broken frame. Which option I choose isn’t just a matter of where I place the edge of the image. It’s really a matter of how the edge interacts with the overall composition of the photo.

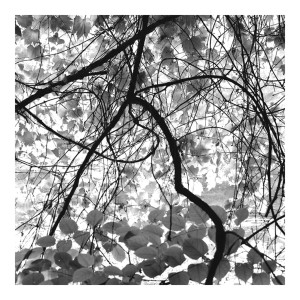

Closed Frame

A closed frame implies nothing outside the frame has any particular relevance to the image. The image is complete unto itself. In general, such images are carefully composed with the attention of the viewer directed toward specific elements. In complex images if the eye is tempted to explore, there are elements to direct it away from the edge and back into the center of the image. Such framing is the most conventional type and is the mainstay of studio work and commercial photography. Closed frame pictures are the closest to pure artifice, creating a reality sufficient unto itself that may or may not have anything to do with the real world the viewer occupies.

Open Frame

An open frame creates the impression that the subject of the image is only part of a larger reality beyond the edge of the picture, as though one is watching life unfold through the arbitrary constriction of a window. It allows for the possibility that the focus of the viewer’s attention may be anywhere within the image, even–in the extreme–outside the image itself. Open frame compositions may appear more chaotic than closed frame compositions and have the effect of making the viewer consider the relationship of the image to the real world of which it is only a limited reflection.

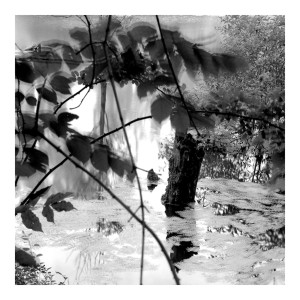

Broken Frame

An image with a broken frame both has and doesn’t have an edge. This is accomplished by printing an image with some white space at the edge so there is nothing to mark the boundary between that part of the image and the paper it is printed on. Such images are rare. When I first began printing in this way, I met with resistance from viewers disconcerted by their inability to tell where the image ended or began. To requests that I reprint such photographs, burning the white sections until a clear edge appeared, I politely declined. It is important to me, in such photographs, that the paper isn’t just a surface on which the image rested but is itself an integral part of the image.

Over time I have become more interested in broken frame, particularly in the photo abstractions of the series Obsessive Emulsion Disorder. Without a clear and complete edge, an image seems not entirely artifice but actually fuses with the world of which it is an assumed reflection. When looking at such an image, we are not only looking at the world through art, we are looking at the world itself. Such images also serve to remind the viewer that when we look at the world itself, we are looking at art of which our consciousness is an essential part.